The Fairhaven Historic District, a town site first platted in 1883, encompasses an area of three and a quarter blocks and contains the areas best preserved commercial buildings. By 1904 Fairhaven and adjoining communities along Bellingham Bay had consolidated to the City of Bellingham. Separated from greater Bellingham by the topographical barrier of Sehome Hill, Fairhaven came to be known as South Bellingham after consolidation.

Fairhaven boasted the city’s most extensive deep-water frontage. When speculators promoted the town site as the anticipated terminus of the transcontinental railroad a sizable business district mushroomed there in 1889-1890. Fairhaven proved to be an ideal manufacturing town because of its ready access to coal and timber. Its lumber and shingle mills and large salmon cannery were among Whatcom County’s prime industries.

Fairhaven’s waterfront is still a manufacturing site, though it is presently dominated by small boat building and repair operations. In Fairhaven the Port of Bellingham maintains its south terminal, a deep-water facility in a protected location accessible by truck and railroad with the potential for handling containerized cargo. Nevertheless, the community’s payroll and population have been in decline since the Post War years. Much of the commercial development, which earlier in the century was nearly continuous along the West End of Harris Avenue to the waterfront, has been razed, and the cleared land remains vacant.

What remains of the once-thriving commercial center is a comparatively small core, which composes the community’s special sense of identity. Thirteen primary buildings oriented along the main intersecting streets of Fairhaven date from the speculative boom between 1890 to the First World War. Two of the three secondary structures were constructed after the historic period, in l919 and 1929. The remaining secondary structure was constructed at an earlier date, but its historical character has greatly depreciated. There are a number of vacant lots within the district, but recent intrusions – such as banking and shopping facilities, service stations and apartment buildings – occur on the periphery, outside district boundaries.

Fairhaven’s business district has enjoyed a recent revival, largely due to the efforts of a private developer who in l973 acquired and renovated for commercial lease the Mason Block, now the focal point of, the district. Subsequently, other landmarks were renovated, and business was buoyed by a succession of tourist-oriented shops and eating-places.

The town site was laid out on a conventional compass-oriented grid, and blocks were subdivided, without alleys, in two common formats. Principal streets with steep grades, such as Harris Avenue, were overlaid with ribbed concrete lanes to provide maximum traction in wet weather. Fairhaven’s electric street railway was discontinued in 1939 and l940, and most of the tracks were taken up for scrap during the Second World War. However, the brick-paved railway bed is still exposed at the centers of 11th Street and Harris Avenue. Brick pavement is exposed in some of the gutters, too. Concrete curbings and sidewalks are typical within the district. Overhead wiring is in evidence today, as in the historic period. However, modern mercury vapor lamps have supplanted historic street lighting. The pervading view from nearly every vantage point is that of Puget Sound to the west.

The common building material is brick, although many of the buildings are of double frame construction merely faced with brick. Typically, surface details reflect Italianate and Richardsonian Romanesque Styles. The two non-commercial buildings in the district, the Carnegie Library and the Kulshan Club, are examples of the Jacobethan Revival and Chalet Styles. Buildings of two and three stories are the norm, and, because of the sloping terrain building heights above grade are almost always greater on the westerly side.

Considerable attrition of Fairhaven’s older commercial buildings occurred following the Second World War. As business and industry was attracted to central Bellingham, population declined, and unoccupied and dilapidated buildings, including a number of frame structures at the west end of Harris Avenue, were cleared away.

The Fairhaven Hotel, an imposing five-story Jacobethan Revival landmark of 1850, which was the pride of Fairhaven, stood on its corner site opposite the Mason Block through the city or Bellingham’s centenary, 1953. Though the old hotel was somewhat deteriorated and altered in appearance by that date, its demolition shortly thereafter left a gap that is still felt at the major intersection of the historic core.

In the late 1930s or early 1940s a short tangential section styled Finnegan Way was constructed immediately north of the business district in order to connect 11th Street, the major arterial from downtown Bellingham, to 12th Street, which merges with the celebrated Chuckanut Scenic Drive toward the south city limits. This project necessitated minor relocation of, the Kulshan Club.

Development, which has had a direct impact upon resources within the historic district, of course, is the renovation movement that had its impetus in l973. All but one of the primary structures have been stabilized and/or refurbished to varying degrees. Projects have ranged from the minimal, which is to say cleaning of exterior walls and repainting of trim, to the more comprehensive, including remodeling of ground story shop fronts, minor modification of openings, alteration of interior space and finish work, and addition of certain external decorative elements. On the whole, changes to building exteriors have tended to be compatible with turn-of-the-century architecture in spirit, if not in detail.

Primary Buildings

Mason Block, 1200-1206 Harris Avenue

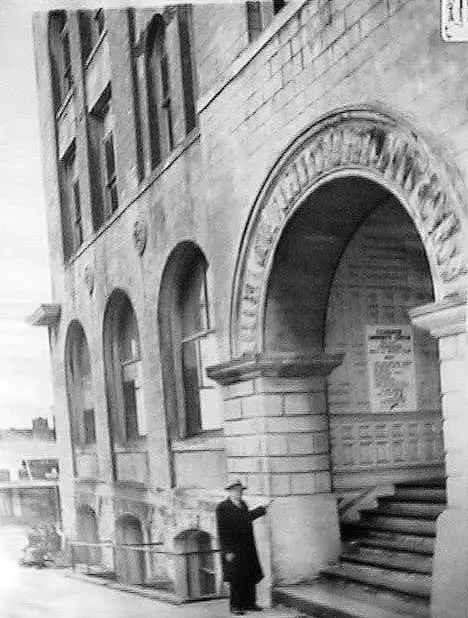

Because of its exceptional size (nearly a quarter of a block), its comparative sophistication and historic role, it is the preeminent landmark standing in the community today. Moreover, the Mason Block renovation gave impetus to the revival of Fairhaven’s business district over the past three years.

The three-story building with stone foundation and brick exterior walls is nearly square in plan. Upper story fenestration in the street facades is a rhythmic arcade in which linteled openings are aligned under varied groupings of round-arched third-story transoms. Piers between bays rise as uninterrupted vertical bands behind which the spandrels are recessed. This fenestration, linked at the top by arches, and the round-arched portal in the principal facade emulate the Richardsonian Romanesque Style. The design clearly is related to the multi-storied Richardsonian Romanesque office buildings that were being erected in Seattle after the Great Fire of 1889. However rudimentary a version it may be, the Mason Block too appears to owe inspiration – at least indirectly – to the much-copied Chicago prototype. Prime, examples of the Richarsonian style are emphasized by the use of molded flat-faced terra cotta whose dark red tone strikingly contrasts with the brick facing. The Mason block has an impressive three-story interior light well, and the staircase and balustrades are carved with stylized ornament in the Eastlake tradition.

Originally, four ground story shops with conventional cast iron fronts were on Harris Avenue – two on either side of the central portal. On 12th Street, a bay window and two lunettes to light the front corner shop broke the ground story wall; and there was another business front at the south end. Over the years the shop fronts were variously remodeled, and openings in the 12th Street facade were remodeled as a round-arched portal to match that of the principal facade, and both entrances were fitted with imported bronze-framed doors. The exterior was sand-blasted, and deteriorated features such as the crest and a corner post of the parapet were rebuilt. The escutcheon title was changed from Mason block to “Marketplace.” Shop fronts were restored along original lines, and the interior spaces around the light well were converted to shop and restaurant use. Perhaps the only obtrusive alteration to the exterior was the addition of a deep paneled, frieze atop the ground story, which extends to grade level as a round-arched frame around-the central portals of either facade.

The Mason Block is said to have been completed, by an unidentified architect, in July 1890 for Tacoma investor Allen C. Mason at a cost of $50,000. Ground story shops were historically occupied by a succession of dry goods merchants, clothiers, grocers, and pharmacists. The shop on 12th Street originally housed the office of leading Fairhaven investment bankers Roland G. Gamwell and Charles F. Warner. The upper stories were originally offices but the rooms in later years were devoted to housekeeping. During the palmy days of old Fairhaven, a suite of rooms on the third floor served as headquarters for the Cascade Club, an exclusive men’s social organization which was host to distinguished visitors to the area, including well-traveled lecturer Mark Twain.

Waldron Block, 1308-1314 12th Street

The Waldron block bears the name of its builder, C. W. Waldron, owner of the Bank of Fairhaven and the man who, in 1890, was reported to have been the largest individual investor in property or the Fairhaven Land Company.

The Waldron Block (ca.-1890-1891) occupies two lots at the northwest corner of 12th Street and McKenzie Avenue. Its height of four stories makes it an exception within the Fairhaven Historic District; however, the upper floors have not been used very much due to a fire that interrupted the reconstruction.

Its arched fenestration, segregated into groups by piers protruding from the wall plane, and rock-faced masonry used on ground story facades suggest that this building also emulated the Richardsonian Romanesque Style, though in a manner less well-conceived than the Mason Block across the street. A three-story rounded bay and a three-centered arch surrounded with a rock-faced masonry are at the southeast corner of the building. Along the 12th Street facade flanked by the original shop, a similar portal set off by stone piers gives access to upper stories. Above the ground story, brick piers frame multi-storied groups of two and three bays and extend, unbroken, slightly above the roof-line where, no doubt, further cornice embellishment was planned. Since 1973 the exterior has been cleaned, the shop-front trim repainted and boards have been removed from unglazed window openings; an attempt to make the upper floors habitable.

Nelson Block, 1100-1102 Harris Avenue

The Nelson Block was built by J. P. Nelson to house a banking establishment. Its upper story was used for professional offices during the historic period. Built in 1900, the Nelson block occupies two lots at the southeast corner of Harris Avenue and 11th Street. It is a late example of the High Victorian Italianate Style with a few up-to-date features, including a huge round-arched portal in the Richardsonian Romanesque tradition. While the building is somewhat retardataire for turn of the century style, it presents the best-preserved and most well designed street fronts in the district.

The Nelson Block is surrounded by a non-projecting classical port of sandstone with an entablature that bears the inscription “Bank” and is supported by fluted pilasters. This entry is reached by a short flight of bowed steps. A large round-arched portal gives access to the upper floor with sandstone archivolt in the 11th Street facade, and a conventional shop front in a wide bay at the outside end of either facade.

Brown facing brick used at this level is highlighted by inlays, which match the cream colored facing brick of the upper story. Second story windows are round-arched and have graduated reveals and sandstone archivolts. The date 1900 is stamped in the parapet of the cornered bay crest. Exterior walls have been cleaned since 1973, and the entablature was painted brown to match the tone of ground story facing brick.

Terminal Building, 1101-1103 Harris Avenue

The Terminal Building is one of the oldest structures in the district, completed by 1890 at the latest. During Fairhaven’s heyday it housed the Sideboard Saloon and G. O. Pearce, barber. The building’s owner adopted the name “Terminal Building” in the 1930s, referring to the intersection of the main electric street railway in front of their store.

The Terminal Building is a two-story simple expression in the High Victorian Italianate Style, with segmental-arched openings. The street facades are constructed with brick veneer while the others are finished with clapboards. Four regular bays light the second story, and the wall plane is recessed behind plain pilasters at either corner. Both street facades are capped by a wooden frieze and bracketed cornice.

The principal facade on Harris Avenue is formally organized, with two ground story shop fronts on either side of a narrow central entry with a three-paneled door. Four regular bays light the second story, and the wall plane is recessed behind plain pilasters at either corner. Either street facade is capped by a wooden frieze and bracketed cornice.

The shop fronts marked off by fluted, or channeled wood piers, are treated somewhat differently. The west shop at the intersection appears to have been remodeled shortly after the turn of the century in the Colonial Revival Style, for it has a classical entablature, a round, tapered corner column, and a chequered transom or colored and diapered leaded panes. Since 1973, the foundation has been reinforced, facing brick has been cleaned, broken windows reglazed, and the cornice painted.

Monahan Building, 1209 11th Street

The Monahan Building was completed in 1890 at a cost of $7000 for Thomas E. Monahan, who maintained it as a respectable saloon. The two-story building with a partial basement is of double frame construction on concrete foundation and is faced with brick.

The building’s facade is in the High Victorian Italianate Style. Rock-faced cast stone pedestals form the bases of ground story piers, which mark off a standard tripartite shop front and a narrow side entry to the upstairs. The second story is lighted by three stilted segmental-arched windows, linked by faceted brick string courses and capped by scrolled sheet metal hoods. The tympanum of the central pediment is filled with brick and is corbeled out over panels bearing the date and the builder’s name.

The ground story front was modified in recent years, but not irretrievably. In 1974 the shop’s ceramic tiled floor was converted to neighborhood theater use. The front was closely restored to its original form, the exterior facing was cleaned and the cornice repainted.

1211 11th Street

1890 is the construction date attributed to the single story building adjacent to the Monahan Building. The facade appears to have been initially remodeled in the 1920s when the building was occupied by a saloonkeeper named Odell. Typical of the period, the building is faced with scribed brick with a single frieze panel in bas relief and a minimal corbeled cornice. The building continued to operate as a saloon or tavern under various names until it was remodeled for restaurant use in 1974. Projecting bay windows in a pseudo-Colonial style were added on either side of the central entry, and the original transom space was filled with vertical wood panels trimmed and painted in a contemporary manner.

Knights of Pythias and Masonic Hall, 1208-1210 11th Street

The Knights of Pythias and Masonic Hall (1891) is a substantial three-story brick masonry building with basement, which emulates the Richardsonian Romanesque Style. The central feature of the ground story is a round-arched entry to upper floors, which are framed with rock-faced sandstone. Originally, it was flanked by two conventional shop fronts, which have since been remodeled. Transom lights have been covered and spandrels decorated with painted paneling. A marquee shelters new bay windows with Roman brick bulkheads, and fronted by freestanding slender cast iron columns.

The upper story openings are grouped as wide outer bays, tripartite intermediate bays, and a central bay composed of narrow paired openings. Surface decoration includes sandstone lintels, recessed frieze panels, and goffered and faceted brick spandrel panels. The fraternal orders housed in the building during Fairhaven’s heyday are named on the central bay’s sheet metal escutcheons. The corbel table, now missing, originally supported an elaborate sheet metal cornice and central crest with broken and scrolled pediment. In recent years the upstairs portion of the building has been used as a rooming house.

1204-1206 11th Avenue

The estimated construction date of the two-story building adjacent to the north wall of the Knights of Pythias and Masonic Hall is 1888. Originally, it was a single story structure with brick exterior and shops on either side of a central entry. In the intervening years the north half of the facade was stuccoed and later extensively renovated. A brick-faced second story was added to the front portion and new shop windows were installed along original lines. The building historically has used been as a store and is the current location of Paper Dreams stationary store.

Morgan Block, 1000-1002 Harris Avenue

The Morgan Block was completed during the 1890 building boom for a reported cost of $8,000. The ground story housed a saloon and a store, and rented rooms were maintained in the upper floors. The building is a restrained example of the High Victorian Italianate Style. Walls are of double frame construction with brick facing on street elevations. Clapboard and composition shingle siding protects the East and rear walls from the weather. Second and third stories are divided by a narrow light well open at the east end.

The Harris Avenue facade is scrupulously symmetrical, with wood-framed shop fronts on either side of a narrow central entry to the upper stories. Segmental-arched openings of the second and third stories are treated as stilted, or straight-sided arches in which brick archivolts with sandstone “knees” are carried below the actual springing line. The facade is divided into three sections by a corbel table and strip pilasters. The third story pilasters and corner piers are embellished with channeled sandstone inlays that are fluting abstractions. A bracketed wood cornice linked by regularly spaced solid consoles, caps street elevations. A few of the original stove chimneys are still intact. An engraving in Fairhaven Illustrated, a publication of 1890, indicates that these originally were joined by a decorative screen, or Darapet, probably of sheet metal, no longer extant.

The west shop front has been modified with a garage door; recent exterior work has been limited to cleaning and repainting.

913-915 Harris Avenue

This two-story brick building with basement was built on the northeast corner of Harris in 1903. It emulated the up-to-date Second Renaissance Revival Style and incorporated several Colonial Revival features. During Fairhaven’s heyday the west shop contained the Jenkins-boys Co., a new and second hand goods store. Around the turn of the century the Elk Bar occupied the east shop corner space.

The east shop has a recessed entry on a diagonal at the corner, and has retained its original wood frame beneath a cast iron beam supported at the corner by a free-standing cast iron column. On the Harris Avenue facade six regularly spaced bays in the form of stilted round arches light the second story. The tympanum of the arches are blind and fitted with tongue-in-groove panels decorated with round bosses, apparently standard millwork of the period. The sheet metal entablature, forms a frieze with rectangular panels corresponding to each bay, a corona projecting over modillions, a parapet, and a scrolled pedimental crest with date panel over the central bay of the main facade.

Around 1945 the upper story or this building was converted for use as a dance hall by Slavs whose forebears, emigrants from the Adriatic isle of Vis, had been attracted to Fairhaven by the fishing and canning industry around the turn of the century. The roof-line wood trusses that were added to strengthen the dance floor are exposed.

909-911 Harris Avenue

1888 is the estimated construction date for this two-story building with brick exterior. It is more likely, however, that the building was contemporaneous with its neighbor and was erected between 1900 and 1903. Its facade is plain has segmental arched windows and conventional shop fronts on either side of a central round-arched entry. When it was cleaned and renovated, a fanciful wood cornice and hood molds were also added. The main doorway still has the original fanlight and a double-leaf door. The eight narrow bays on the second story are not regularly spaced, but grouped so that paired windows alternate with single openings. After the Second World War, when business was drawn away from Fairhaven to central Bellingham, this building, like its neighbor, came to be used as an industrial shop.

1408-1410 11th Street

On the northwest corner of the intersection of 11th Street and Larrabee Avenue is a two-story building dated at 1890. Its precise original use is not certain, but earlier in the 20th Century it was occupied by saloon keeper Michael Grad. Later, it was used as a duplex, and an automobile garage occupied the south portion of the lot.

The second story of the simple Italianate building is essentially intact. The double frame building has a stone foundation with a brick veneer and some clapboard siding on the south elevation. A comprehensive renovation included refinishing the interior, remodeling the ground story front, repainting the red exterior, and laying a brick pavement in front.

Carnegie Library 1105 12th Street

The compact grounds of the Carnegie Library are planted with lawn, evergreen shrubbery, mature cedars, and five ornamental trees lining the parking strip. The one-story building with basement was based on a design in the Jacobethan Revival Style by the Seattle firm of Elliot and West.

The high ground course of cast stone imitates rock-faced masonry, with walls of concrete block and brick. A shingled gable roof overhangs the facade on either side of a central projecting section that terminates in a Jacobethan gable with stepped shoulders and crown. Three double-hung sash windows with diapered leaded panes light the gable of the central section of the facade. The original chromatic effect produced by dark red walls and contrasting light stone and painted wood trim is correct for the English Renaissance architectural period. However, it was sacrificed during the refurbishing that covered the exterior walls with a thin layer of cream-colored stucco.

Now a branch of the Bellingham Public Library, Fairhaven’s facility is an outgrowth of a reading room established by private citizens as early as 1890 and operated at various locations, including the Mason Block. After 1892 the library gained, fluctuating public support and continued to operate in the Mason Block. Shortly before voters approved consolidation with Whatcom in 1903, Fairhaven appealed to Andrew Carnegie for funds to erect a library building. A total grant of $16,000 was received; C. X. Larrabee donated the lots; and a local contractor who modified the plans of Elliot and West completed the library in December 1904.

Kulshan Club, 1121 11th Street, 1120 Finnegan Way

When the Kulshan club was built in 1909, it was originally located directly across from the Carnegie Library. It was moved to its present location in the late 1930s or early 1940s when Finnegan Way was created.

The ground story is clad with horizontal boards and battens and is further embellished with wooden panels, quoin-like at the corners. The upper story is clad with cedar shingles, the bottom course of which has fancy butts. The building retains most of its initial coloration which was brown highlighted by white-painted trim. The former clubhouse, now known as the Seaview Apartments, was converted to apartment use in 1942-1943.

Named after the Native Indian name for nearby Mt. Baker, the Kulshan Club, successor to the Cascade Club, was Fairhaven’s leading men’s social club. The Kulshan Club was organized in the Mason Block during the summer of 1904. Early in 1909 the new group acquired a building site on 12th Street opposite the Carnegie Library and called for bids. The clubhouse was planned in the Chalet Style by the firm of Cox and Piper, and the project reportedly completed that summer for a cost of about $5,000.

Born and trained in England, F. Stanley Piper designed a number of Bellingham landmarks, including the Herald and Bellingham National Bank Buildings. Piper arrived in the United States in 1907, and after spending two years with a Seattle firm, he moved to Bellingham and entered into practice with local architect William Cox. Piper later worked in association with T. H. Garder, and the partners maintained affiliation with the Royal Institute of British Architects.

In 1929 the clubhouse was the scene of the organization of the South Bellingham Community Improvement Club which, during the Great Depression, undertook the important work of grading and surfacing unimproved sections of Fairhaven’s dedicated streets.

Secondary Buildings and Sites

1304-1306 11th Street

The estimated date for the construction of this building is 1890, however, it may have been built slightly later. More recently, the building was modified to house the Fairhaven post office and a variety store. Any decorative treatment, which may have existed along the roofline, has been removed. Exterior facing varies on each elevation and includes brick, stucco and composition siding. Anticipating additional development on the block, a stone pavement was laid along the base of the south wall, and antique street lamps were added as accents.

Now vacant, the lot on the southwest corner of the intersection of 11th and Harris Avenue was the site of an important commercial landmark the office building of early Fairhaven real estate brokers Riedel and Moffat. The distinctive feature of this two-story Italianate building was a three-story corner tower with bracketed cornice and square ogee dome. Existing through the 1920s, the demolition date of this building is unknown.

Directly across Harris Avenue from the site of the Riedel and Moffat office building is another vacant lot, which is the former site of the three-story Italianate Citizens Bank Building. Built in 1890, the bank was headed by the influential C. X. Larrabee. Engraved illustrations of both of the vanished landmarks are included in the 1890 publication Fairhaven Illustrated.

1112-1114 Harris Avenue

This one-story building with basement presently known as Finnegan’s Alley was constructed as a garage in 1919. It has a concrete foundation, brick walls with stucco exterior finish on street facades, and a wood truss roof with an arched profile and clerestory end windows. Uprights between bays are extended above the parapet as short posts with segmental-arched heads. The building was later renovated to house shops and restaurants. The overall effect of the exterior remains more or less unified, despite a certain disparity in the treatment of individual shop fronts. “Finnegan’s Alley” is included as a building of secondary significance because it has occupied the focal intersection for over fifty years and its current use is consistent with land use in the historic district today.

1111-1115 Harris Avenue

In 1929, the single-story building with basement at the northwest corner of Harris Avenue and 12th Street was constructed of concrete with a stucco exterior finish. Strip pilasters continued as short posts between low pedimented parapets mark off the 25-foot bays. Shop fronts are organized in the conventional manner with transom lights, marquee, and central entries between display windows. Except for a coat of turquoise paint, the corner shop occupied by the Fairhaven Pharmacy is unaltered. The fronts of 1111 and 1113, now painted light tan, have been modified slightly. The building has been given secondary significance status because it has occupied the focal intersection of the district for nearly fifty years and houses the successor of an historic local business.

Daniel J. Harris and the Founding of Fairhaven

The “mainspring of all enterprise” in Fairhaven after the era of Daniel Harris was the Fairhaven Land Company, a subsidiary of the Fairhaven and Southern Railway. It was incorporated in Tacoma in November 1888 with capital of $250,000. Company President C. X. Larrabee, who had made a fortune from a silver mine in Montana, and capitalist Nelson Bennett were the guiding spirits of the new venture. With them were those who built landmarks still standing in Fairhaven – men such as J. F. Wardner, Roland G. Gamwell and C. W. Waldron.

Bennett completed not only the large purchase of Harris’s townsite, but acquired the adjoining Bellingham townsite of Erastus Bartlett and Edward Eldridge, property at Whatcom held by the Kansas Colony, and scattered claims along the bay as well. This “immense deal”, predicated on the transcontinental railroad terminating at Bellingham Bay, signaled a real estate boom which continued for two years. A brickyard was started in Happy Valley, east of Fairhaven, and Bennett placed an initial order of 1,000,000 bricks. Other factories and mills were started to supply the demand for building materials. Fairhaven became the construction center for railroad lines being built south into Skagit County and north to British Columbia. Waterworks and other public utilities were planned. Advertisements were placed in Seattle, Tacoma, Portland, and New York newspapers; circulars were sent abroad to Germany. By the spring of 1889, business lots in Fairhaven were selling for between $1,000 and $1,500. In 1890 a crown project of the company was completed: construction of an imposing five-story Jacobethan Revival hotel in the tradition of grand railroad hotels. The Fairhaven Hotel stood at the town’s major intersection through the centenary observed in 1953, but was torn down soon after.

In time, it was clear that Seattle would be the important railhead port on Puget Sound. Nelson Bennett and several of his syndicate associates sold out, and in the depression following the nationwide Silver Panic of 1893, Fairhaven’s dizzying growth came to an end.

Events Following the Boom and Panic

Fairhaven, which had been consolidated with the old Bellingham townsite since 1890, boasted the best deep-water wharves on the bay; the Great Northern, Northern Pacific and Bellingham and British Columbia Railroads to destinations south and north linked it. Moreover, it was juxtaposed with vast timber lands and promising gold mining districts. As the turn of the century approached, the town emerged from the economic slump as a vital manufacturing center. Following final municipal consolidation and the creation of the City of Bellingham in 1904, the list of Fairhaven’s industries included a big lumber mill, foundries boiler works, machine shops, and the region’s largest shingle mill, which produced as many as 150,000,000 shingles annually. In addition, an immense salmon packing industry with satellite canneries in Alaska was centered in what then came to be known as South Bellingham.

C. X. Larrabee retained control of the old Fairhaven Land Company, eventually reorganized the Pacific Realty Company, and he directed a number of public improvement projects. Not least of these was development of Fairhaven Park on land that he and others donated. A plan for the 16-acre park was drawn in 1910 by none less than the Olmstead Brothers firm, but it was not carried out in detail.

Over the past thirty years, as business and industry were increasingly attracted to central Bellingham, Fairhaven’s industrial payroll and population declined. Unoccupied and dilapidated buildings between the business core and the waterfront were cleared away. The bayfront is still active, however, as a small-boat building and repair site, and the port of Bellingham maintains there its south terminal. The business district has been claimed in recent years largely through the efforts of Kenneth Imus, a Fairhaven native and private developer who, beginning in 1973, acquired and renovated a number of properties in the historic district for commercial lease. Other property owners followed suit, and business in the older structures was revived by a succession of tourist-oriented shops and eating-places.